Why

the Oasis?

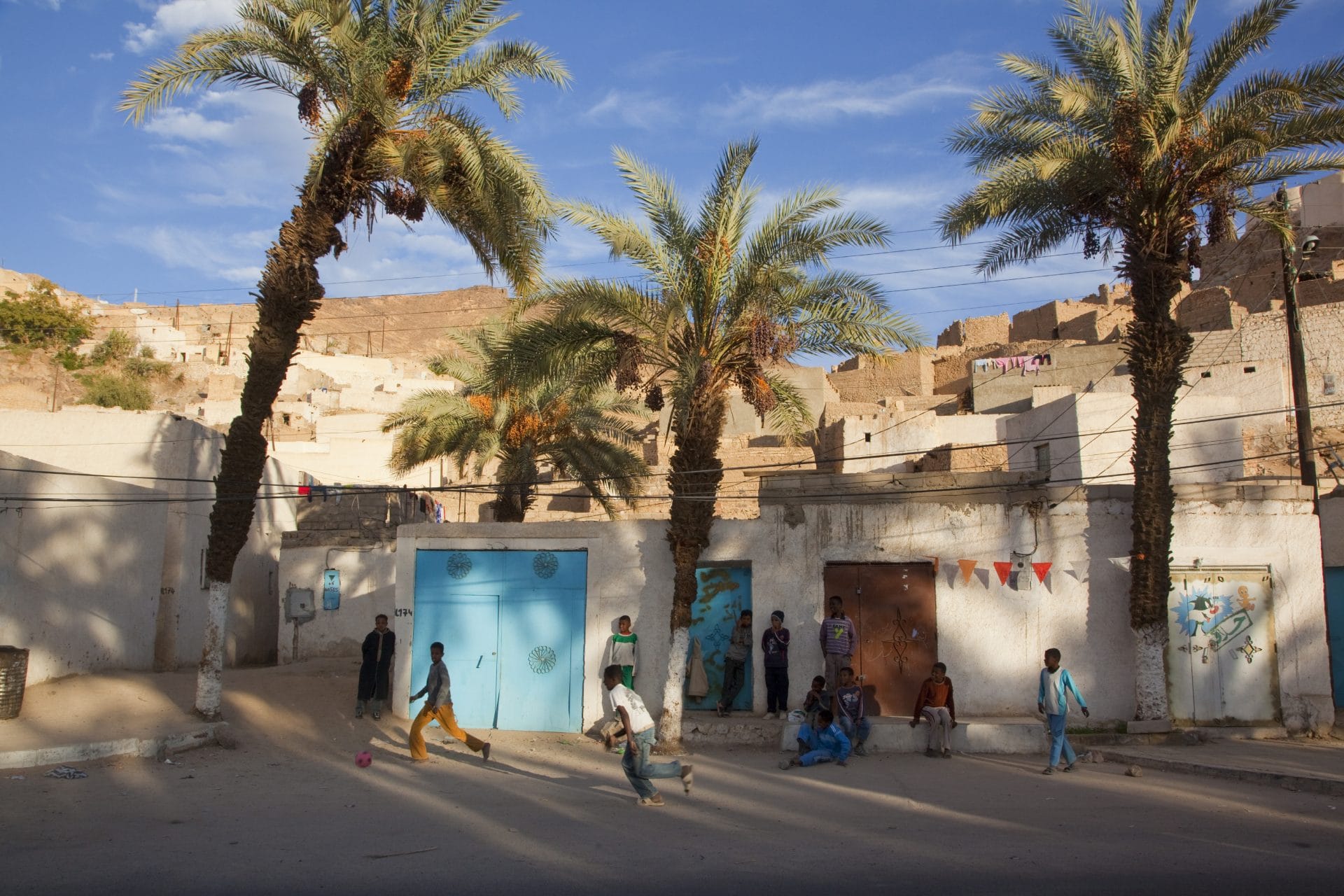

At sundown, youngsters play football in Djanet, the capital of the Tassili n’Ajjer, which is a vast rocky plateau and home to the archaeological park of worldwide significance. As a matter of fact it is here that numerous cave paintings – since 10,000 BC – illustrate mankind’s life styles in prehistoric times. Djanet was founded no earlier than the Middle Ages, by the same Berber nomadic populations that still live there and speak the tamahaq language, the Kel Ajjer Tuaregs. It is nestled in the bank of the wadi Idjeriou, overlooking an extensive date palm grove from a height of 1000 m.

Overview of the Oasis’ luxuriant palm groves in the valley carved by a wadi, the prehistoric river. The small Oasis hosts an important heritage of forestry, the result of the work of generations, but the scarcity of water, that can now only be found by digging deeper and deeper, is threatening it. Every day before sunset, the concomitant use of many diesel motor pumps – which extract water for irrigation from too many individual wells – is not only polluting the air, but also spreading diseases that damage crops.